A Homeowner’s Guide to Water Heaters: How They Work and What to Know

Aloha and Welcome back to Energy Horizons!

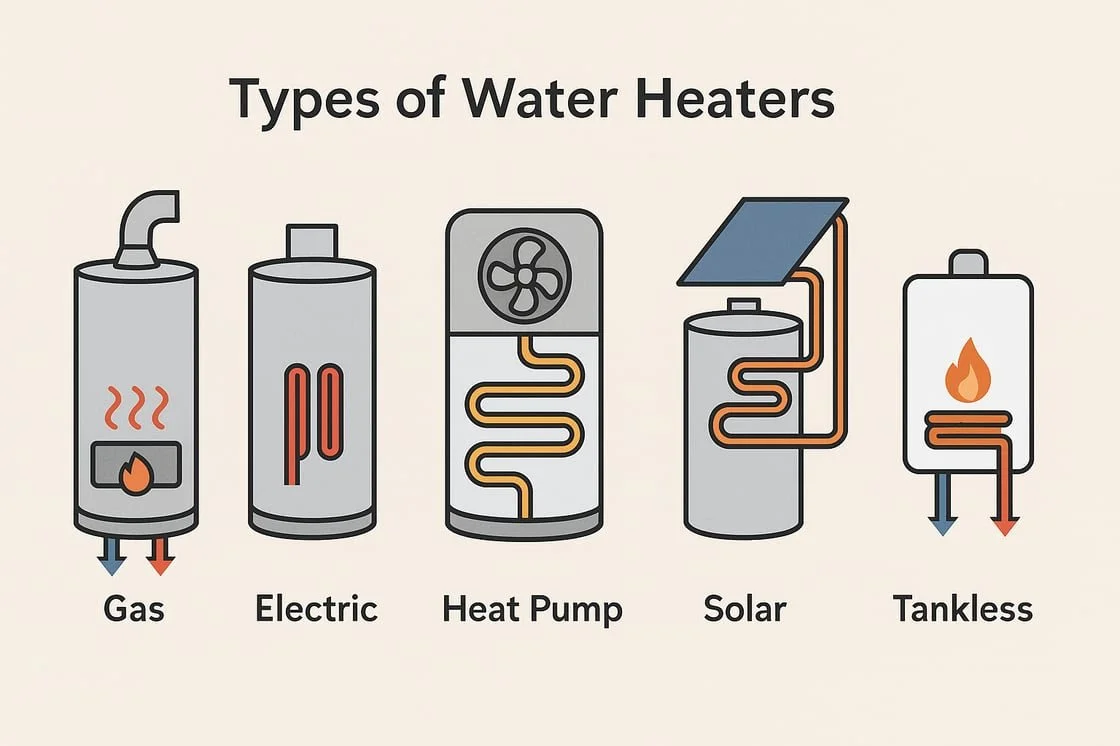

For most of us, hot water is something we don’t think much about—until the shower runs cold or the water heater stops working. Behind the scenes, a water heater is one of the most important appliances in your home, quietly providing hot water for showers, laundry, dishwashing, and cleaning. Understanding how different types of water heaters work can help you make smarter choices when it’s time for a replacement. The most common type is the traditional storage tank water heater. These come in gas and electric models and work by keeping a large amount of water—usually 30 to 80 gallons—hot and ready at all times. Cold water flows into the tank, where it’s heated either by a gas burner at the bottom or by electric heating elements inside the tank. As hot water is used, more cold water enters and the heating cycle continues. They’re relatively affordable to install and straightforward to maintain, but because they heat water around the clock, they lose energy to “standby heat loss,” meaning you pay to keep water hot even when you’re not using it.

An alternative to the tank is the tankless water heater, also called an on-demand unit. Instead of storing water, these systems heat it instantly as it passes through a heat exchanger whenever you turn on the hot tap. Because there’s no tank keeping water hot 24/7, they can be more energy-efficient, and they take up less space. Tankless systems can supply an endless stream of hot water, but they have limits: running multiple showers and appliances at the same time can overwhelm them. They also tend to cost more upfront and require periodic maintenance, especially in areas with hard water. A newer option gaining popularity is the heat pump water heater (HPWH), sometimes called a hybrid. Instead of creating heat directly, these systems pull warmth from the surrounding air and transfer it into the water—similar to how a refrigerator works in reverse. Because moving heat is more efficient than making it, HPWHs can use up to 70% less electricity than standard electric models. They work best in warm or moderate climates and require a bit more space for airflow. While the initial price is higher, the energy savings can be very significant over time. For homeowners in sunny areas, solar water heaters offer another approach. Roof-mounted solar collectors absorb heat from the sun and transfer it to the water, either directly or through a fluid that runs to a storage tank. On cloudy days or at night, a backup heater takes over. Solar systems have the potential to drastically cut water heating costs and reduce environmental impact, but they do require a sunny roof, a larger upfront investment, and occasional professional servicing. Each system comes with trade-offs in cost, efficiency, and maintenance. Conventional storage tanks are affordable and reliable, but less efficient. Tankless models save space and energy, yet have limits on simultaneous use. Heat pump water heaters offer big savings, while solar models can provide very efficient hot water if your home and budget allow for the installation. No matter the type, regular maintenance—such as flushing the tank or descaling the heat exchanger—can extend the life of your system and keep it running efficiently.

By understanding the strengths and limitations of each water heater type, you can make a choice that balances comfort, efficiency, and cost for your household. That way, your next shower will be as warm and worry-free as you expect.

Keeping Cool and Saving Energy: A Homeowner’s Guide to Air Conditioners

The summer heat is here, and your air conditioner is the most important appliance in your home. Whether you have a central system, a window unit, or something in between, the way you use and maintain it can make the difference between a comfortable home and a sky-high electric bill. Understanding the main types of A/C units and how to get the most from them can help you stay cool without overspending.

The most common whole-house option is the central air conditioning system. This uses a network of ducts to push cool air into every room, with a central thermostat controlling the temperature. Central heat pump systems work similarly but can also heat your home in winter by reversing the flow of refrigerant. While these systems offer consistent comfort, they can also waste a lot of energy if your ductwork leaks or your thermostat is set too low for too long. Sealing ducts, programming your thermostat, and scheduling regular maintenance are key to keeping costs down. For homes without ducts, mini-split systems—also called ductless units—provide targeted cooling. Each indoor unit mounts on the wall or ceiling and connects to an outdoor heat pump. They’re great for cooling specific zones in your home and avoiding the energy loss that comes from ductwork. If you have a mini-split, adjust the settings room-by-room so you’re not cooling spaces you’re not using, and keep the filters clean for maximum efficiency. Window units remain a budget-friendly choice for single rooms. They’re easy to install and can cool a space quickly, but older models can be quite inefficient. Newer heat pump window units are changing the game by offering both cooling and heating in one package—using far less electricity than older designs. Whatever type you have, make sure the unit is properly sized for the room; too small and it will run constantly, too large and it will cycle on and off without dehumidifying properly. Portable air conditioners are a flexible solution for renters or for rooms where a window unit won’t fit. They roll from room to room and vent hot air through a window kit. While convenient, they often use more energy than similar-sized window units. To make them work better, keep doors closed to the cooled space, shade the windows, and avoid placing them in direct sunlight.

No matter what type of air conditioner you use, the basic rules for saving money and energy are the same. Set your thermostat to the highest comfortable temperature—typically around 76–78°F when you’re home, and higher when you’re away. Use ceiling fans to help circulate air so you can set the temperature a bit higher without losing comfort. Keep windows and curtains closed during the hottest parts of the day, and open them at night if outdoor temperatures drop. Clean or replace filters regularly, and if your system has programmable settings, use them to cool only when you need it.

Small changes in how you run your air conditioner can add up to big savings over the course of a long summer. By understanding the type of system you have and using it strategically, you can keep your home cool, your energy bill in check, and your equipment running longer.